My husband, Sergey, is from Moldova, though it has now been more than a decade since he lived there. Before he left, his few family members also emigrated—his brother to Russia and his mother to the United States. Until recently, I hadn’t had the opportunity to meet his brother. We had planned to visit Russia while I was in grad school, but then the pandemic began, and then the terrible war in Ukraine, and the prospect of setting foot in Russia dimmed. So, when Sergey heard that his brother, sister-in-law, and their children would be coming to Moldova, we took the rare opportunity to see them. Given the effort of getting to Eastern Europe, it only made sense to add stops so Sergey could visit Moldovan friends who had emigrated to Romania and Germany.

In the midst of time with Sergey’s family and friends, and on days when I wasn’t in bed contending with the foodborne bacteria and airborne virus that in quick succession welcomed me to Eastern Europe, I limned some word portraits of the three cities where we stayed: Bucharest, Chisinau, and Munich.

Bucharest, Romania

Downtown, a constant river of cars flowed. Their exhaust, combined with the cigarettes smoked endlessly by nearly every pedestrian, created a lung-burning miasma. More pleasant than breathing the city air was watching the fashionable young urbanites, dressed in sleek wool coats and enormous scarves, frequenting the numerous coffeeshops and pizzerias until late at night, sitting (and of course smoking) outdoors even as temperatures approached freezing. Sergey’s friend introduced us to a Romanian bakery chain called French Revolution, which creates colorful, exotically flavored eclairs.

Big cities like Bucharest overwhelm me with their frenzied consumerism and often troubled histories. Few cities in Europe escaped the fury of the world wars or the divisions of the Cold War. While today, Romania is a democracy and European Union member, for decades, it was ruled by an autocrat who let his people starve while enriching himself. In the middle of Bucharest, he constructed an absurdly huge palace that is apparently the world’s heaviest building; as we saw from a car, it is now rivaled by a mammoth Orthodox church that is under perpetual construction.

Chișinău, Moldova

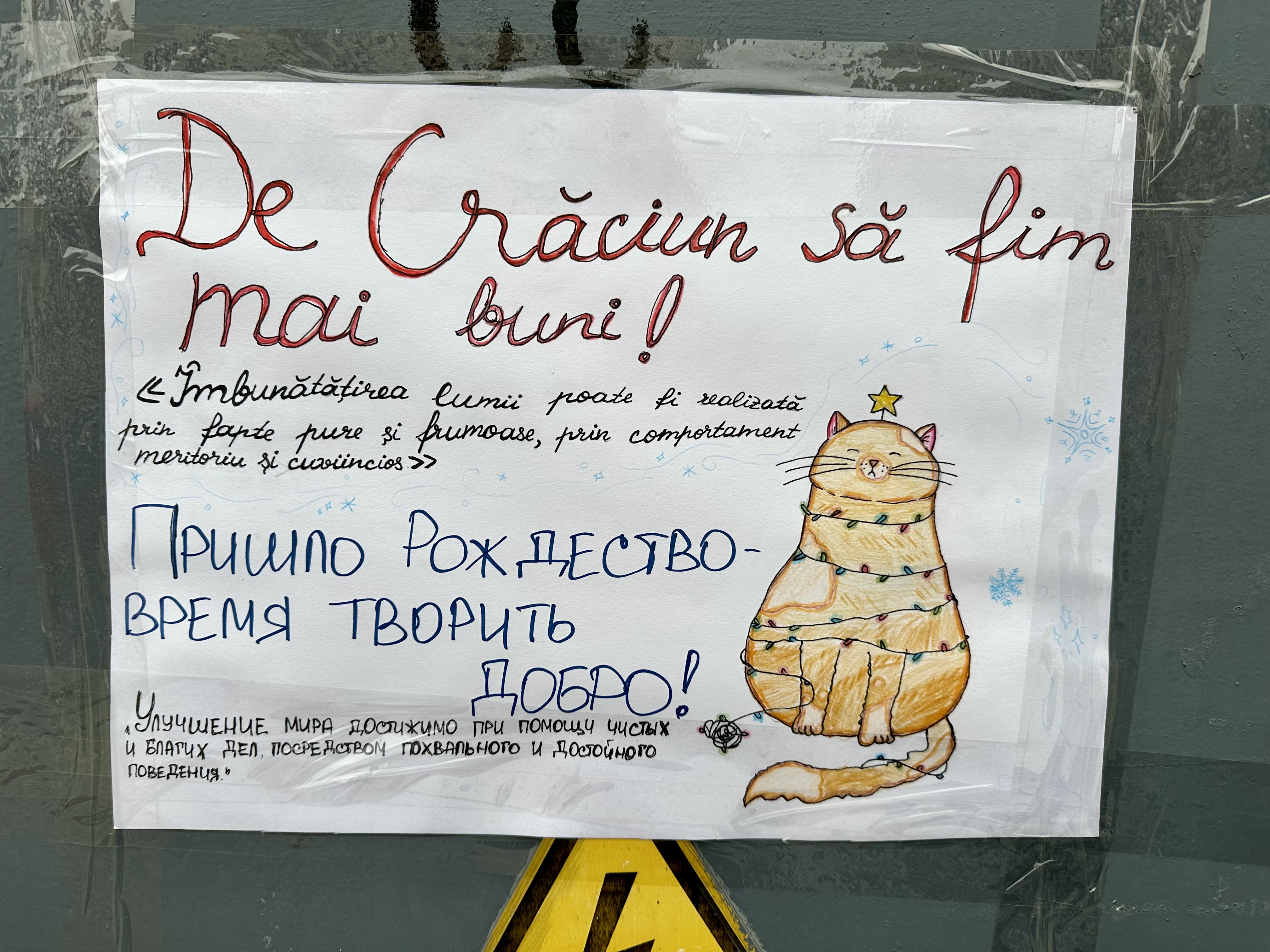

Chișinău or Kishinev? Romanian or Russian? What struck me most about this city was the languages. Although “Moldovan”—which is very similar to Romanian—is the country’s official language, I heard a lot of people speaking Russian. The language question is highly political in Moldova, especially now, when some might equate speaking Russian with supporting the Russian government. Looking at the grannies in their traditional headscarves and dresses, I thought about how many changes, linguistically and politically, they’d witnessed over their lifetimes. The desire to look westward toward the EU and capitalism was displayed downtown with boutiques and a winter festival, whereas in parts of the city including Sergey’s longtime neighborhood, massive apartment blocks from the Soviet era still dominated, gray and grim.

I had been looking forward to finally trying bakery-made plăcintă, a savory pastry that Sergey’s mom had prepared on visits. It commonly comes with three fillings: potatoes, cabbage, or a feta-like cheese. I ate as much plăcintă as possible during our stay; it was readily available at both restaurants and coffee stands. A new discovery was ceaiul de cătină, a tea made with sea buckthorn berries, which emit a glowing orange, tart juice. Delicious!

Munich, Germany

With only one day in the Munich area, my main interest was in visiting the nearby Dachau Concentration Camp to honor the victims of the Holocaust. I learned that this camp operated from 1933 to 1945—such a long time, and so many sufferers. The people the Nazis imprisoned here were worked to the point of death, including on a farm at the edge of the camp that grew produce including tea and spices. One image that stayed with me was a colorful tea tin label proclaiming “Dachau tea.” I imagined Germans during World War II making cups of tea that had been cultivated by half-dead prisoners, who themselves would never taste anything so refined in the camp. The camp gates say, “Work will set you free.”

After we completed a guided tour of the buildings of horror, we went to central Dachau, which looked like a fairytale town with its colorful stucco buildings and cobblestone lanes, all impeccably maintained. As we thawed out in a coffeeshop in Dachau Palace, we contemplated the contrast between this quaint Bavarian town and the nearby death factory.

Epilogue to the Travelogue: Migrant Tongues

Innumerable thinkers have contemplated language’s role in human life. How much does it shape our thought? Does it determine our worldview entirely, or merely tinge our perception? How deeply does our identity sink its roots into the loam of our mother tongue? In a transnational marriage like mine, English is the couple’s common language. But only one spouse has the benefit of speaking it natively.

Recognizing the imbalance, I have so far made two attempts to study Russian. In the first semester of grad school, I audited a beginner class. I got as far as trying to learn how to write Russian in cursive before I realized I couldn’t both succeed in my rhetoric and composition studies and learn a challenging language. Toward the end of grad school, as my workload lightened, I used Duolingo to learn basic vocabulary, but eventually my learning plateaued and, demotivated, I gave up.

From my twice-abandoned studies, I remember a smattering of simple nouns, which enabled me to understand about every tenth word in the conversations Sergey had with his friends and family on our trip. As I’m a quiet person even in English, it didn’t bother me to take a break from conversing. Plus, I have always enjoyed hearing Sergey speak Russian. Listening to an unknown language is like appreciating music—sounds and feelings rather than information. Russian is an especially musical tongue to my ear with its plush sibilants, as in the increasingly endearing diminutives of the name “Sergey”: “Seriozha,” “Seriozhenka,” and “Seriozhenchka”!

If language, perception, and identity form a sacred braid, what to think when Sergey says he’s started to think in English, to forget Russian words? For me, it came as a relief to hear Sergey speak easily with his loved ones, who formed the best destinations on our journey.